(*) ROTISSERIE: Looking beyond our "illegitimate season"

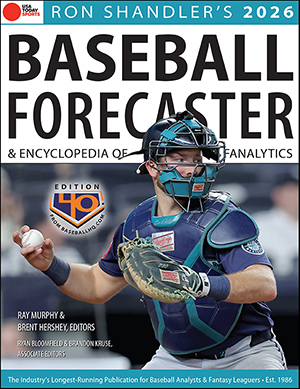

Note: Ron Shandler is the founder of BaseballHQ.com, author of the yearly Baseball Forecaster. This article first appeared on his current site, babsbaseball.com.

They say, “Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it.” When it comes to Major League Baseball, perhaps the opposite is true: “Those who are beholden to history might be doomed to be stuck in it.” Or better – “Those who are beholden to history might be doomed to miss opportunities for positive change.”

For certain, MLB is not one to embrace change easily. Over the past few decades, change has come in fits and starts. Still, even with the heresy of designated hitters, interleague play and wild card teams, the sport has survived.

However, when faced with a 60-game truncated season – one that does not change the essence of the games, only the number of them – it is as if the sky is falling. With all the players and fantasy leaguers reportedly taking a pass on 2020 baseball, you’d think we’re approaching the end of modern civilization as we know it.

The real problem is our relentless grip on history. Tradition and nostalgia keep us tethered to the past, but we are not the same people as our ancestors of 140-plus years ago when organized play began. The world is different. Society is different. Life is more fast-paced. We crave immediate gratification and have shorter attention spans. To cling to the same pastoral game we played at the turn of the previous century makes me wonder if we are stuck in history.

Perhaps we should take a different perspective and embrace the world as it is now. Perhaps we should feel gratified that the traditional game played by the pioneers had a great 144-year run, but now it’s time to move on. It would be nice if the pandemic has the sole redeeming quality of forcing us to see things differently, sparking change.

I doubt that would happen. Still, we could imagine a world where we toss off the shackles of the past and recast the game for today’s mindset. I’m not suggesting we tear it all down and start over; I’m just wondering whether we might have a better game with a few “tweaks.” Traditionalists will scoff, but none of the following would significantly alter the essence of the game.

Yes, the season is too long anyway

The core complaint is that 60 games is not a real season. It’s too short. The statistics won’t be representative. It’s illegitimate. Bring out the asterisks!

Sure, it’s short. But I can’t help seeing that as a good thing. For one, assuming the virus allows us to get in all 60 games and the post-season, we will still have baseball this summer. Given the enhanced importance of each individual game, it’s not unreasonable to expect that the season could be moreexciting.

Consider that the month-long pennant race we used to enjoy would now encompass fully half the season. We could be watching playoff baseball all the time. And with more teams conceivably in the hunt – from the benefit of variance alone – the end result would be more interest overall. How is that a bad thing?

As for the numbers, who cares? Yes, there might be a .400 hitter or a starting pitcher with a sub-1.00 ERA. I think this short season will help us focus less on the numbers and more on the competition. In the end, it’s all about wins and losses anyway.

And as a side benefit, the modified schedule has forced geographic match-ups to be a core part of the regular season. These are natural rivalries that should be expanded! Sure, the American and National League divide has been a part of the game forever, but where is the downside of fostering more subway and interstate series? Frankly, as a Mets fan, I’d much prefer to see far more games against the crosstown Yankees than those odd series against Kansas City or Seattle (no offense intended to those great cities).

Now let’s take it to the next level. If we can experience a “full” season of excitement in two months, why not do it multiple times during the traditional six-month period? We could take the lead of reality TV and fit two or more seasons in the calendar year. If “Survivor” can find success fitting 40 “seasons” into 20 years, why not baseball?

Some time ago, I suggested that we could fit three legitimate seasons in our six-month window. Each season would be 50 games, followed by an off-week for intensive analysis and preparation for the next 50-game block. Each division’s block winner would get a play-off spot, plus one wild card team with the best overall record covering all three mini-seasons. Teams that win multiple blocks would get playoff byes.

For those who still cringe at the statistics that are going to characterize 2020, the tri-block idea would give us a nearly comparable 150-game sample to help maintain some connection to history.

Essentially, pennant race baseball is the most exciting baseball, so the more often we can do it, the better.

Yes, the games are too long anyway

I have been writing about baseball for more than three decades and I have to admit that I have trouble maintaining my attention over the current 3-4 hour spans. Games have become chess matches, with long delays between moves, and short bursts of action.

I suppose that is not too unlike football. However, a large percentage of baseball plays have been reduced to the “three true outcomes” – walk, strikeout, home run – which are really the antithesis of “action.” We need to reimagine a more exciting contest, or at least one that is easier to sit through.

It might start with a 7-inning ballgame. Beyond just reducing the time commitment, it would potentially change in-game strategies and tactical play. Sitting back and waiting for a big inning might give way to more small-ball. Small-ball is exciting.

I am not a fan of the new extra-inning rule that puts a man on second base, but a 7-inning game might mitigate the need of even thinking about that. And as much as I personally abhor a pitch clock, sadly, I think its time has come. Let’s get us in and out of the stadium in under two-and-a-half hours so we can spend more time and money patronizing local post-game watering holes.

Yes, we’re stuck in artificial roles

With the recent changes to pitcher usage, particularly the introduction of the “opener,” it begs the question, why do we have roles at all? Shouldn’t the best players be put in the best position to help a team win games?

So I would dispense with starters and relievers, and just have pitchers.

This is not a new idea. In 1997, in Bill James’ Guide to Baseball Managers, he wrote: “Baseball freethinkers have long-discussed the possibilities of abandoning the roles of ‘starter’ and ‘reliever’ and using all the pitchers on the staff in two or three inning stints.” This was noted under the category of “Stunts.”

But I was intrigued by the idea and wrote about it in a 1997 article, using a computer simulation to micro-manage a team through a 162 game season. I chose the 1996 California Angels, who finished a disappointing 70-91 after contending the year before. The goal was to use a 9-man pitching rotation (three per game in 2-3 inning stints) and manage their in-game usage in order to improve on the Angels’ 5.30 team ERA.

One of my micro-managing rules was that no pitcher would be left in a game to allow more than four runs in a given outing. That meant, if a pitcher had allowed two runs and then put two baserunners on, he was immediately pulled, even if it was in the first inning. This strategy helped to improve Jim Abbott’s ERA from 7.48 to 5.11.

It also lowered the Angels’ team ERA to 4.89, improved all their skills metrics and won them seven more games.

Yes, it was an isolated simulation, but the “stunt” offered hope that a modified approach to roles could improve performance. In addition, the tactical implications made for a more interesting game experience.

It doesn’t stop at pitchers. We are already seeing more fluid use of players in general. Defensive positioning has changed the game and we’re still waiting for batters to effectively counter. More players are playing multiple positions, which offers managers additional flexibility. We can thank advanced metrics for opening our eyes to more possibilities.

Needless to say, all of the above ideas are a pipe dream. Not only would owners and players object, but many fans would too. It’s not that these enhancements wouldn’t potentially make the game better, but they would require too much effort to get enough people to agree to them.

Change is hard. The stubborn preservation of tradition has led to parochial decision-making. This is a great game but it can be improved to better meet the mindset of today’s generation of sports fans. For a start, we should fully embrace this 60-game season and see the potential it could bring to change the game. It’s going to be an exciting two months.